He began that in 2010 and, four years later, started his PhD in Geophysics, which he finished early in 2017.

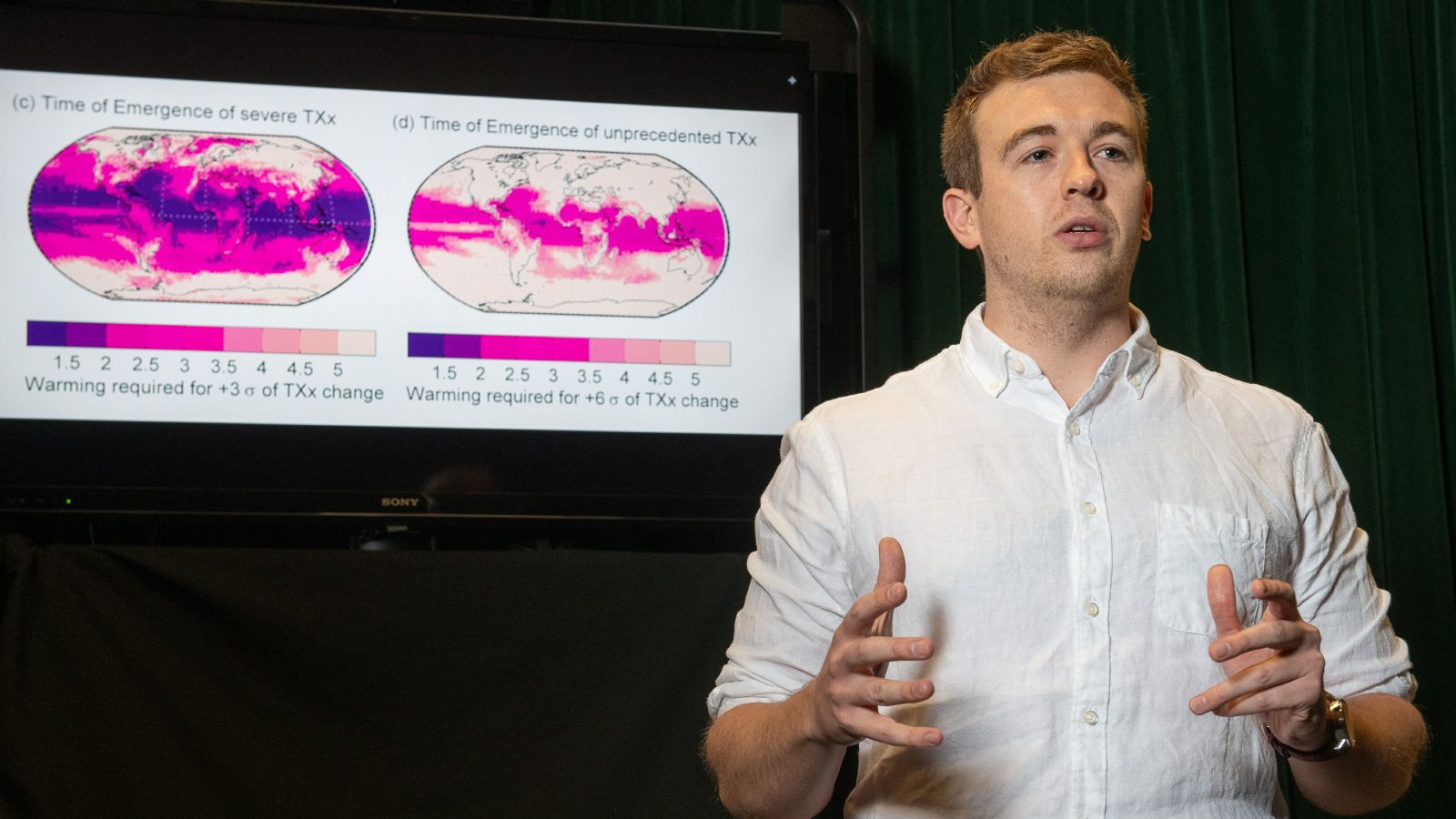

“My PhD was looking at ways to quantify what we call the ‘emergence’ of climate change, which is basically what I’m doing now—trying to come up with clearer ways of identifying when it is we can see climate change as a phenomenon emerging from the norms of our regular weather.

“As part of that, there’s what we call ‘extreme-event attribution’. This is a discipline which has got very large in the last 10 to 15 years, and it’s basically trying to say, when an extreme weather event occurs, what was the role of climate change in making that happen?” he says.

“The basic method is to have many repeated simulations of the climate of today and look at how often an extreme weather event, like the one you are interested in, happens.

“When we repeat the process, we remove all greenhouse gas emissions and other human influences on the climate from the model setup.

"In 1,000 simulated years of the present-day climate, we might witness a summer with a bad drought 10 times. But in another 1,000 simulations of New Zealand summers, this time in a hypothetical climate without humans, we might see a bad drought happen only five times. Therefore, we would say there has been a doubling in the chances of experiencing a bad drought because of those human influences on the climate.”

The Institute is slowly forming a Southern Hemisphere hub to complement a group called World Weather Attribution (WWA), coordinated from Oxford in the United Kingdom, Luke says.

Before returning to Te Herenga Waka in January, he spent four years at the University of Oxford, working closely with the global coordinator of WWA, Associate Professor Friederike Otto, refining the methods and assumptions behind attribution science.

To date, the group has carried out its attribution studies on the largest events affecting the most people across the world.

“But this southern hub is now working hard to develop a protocol so we can finally offer specific numbers about the role of climate change on extreme weather in New Zealand soon after individual events happen.

“Generally speaking, it has been difficult to fund that sort of work. People like to fund cutting-edge, high-profile publication science, which is developing the methods. And people like to fund weather forecasting. But in the middle ground, where it is an operational thing and every analysis might not be exciting or new but is still useful, finding the resources can be really hard.”

In the climate-change stakes, extreme heat is the factor way out ahead of the rest, he says.

“I can’t stress that enough. The headlines will say extreme heat and extreme flooding are both being made worse by climate change. But if you dig into the details, we know that extreme heat is being made worse because of climate change way, way faster, and way, way more severely, than extreme rainfall.

“For some heatwaves, we might see it is as much as hundreds of times more likely today versus in a world without climate change.

“But for hydrological extremes, extreme rainfall, or extreme drought, you are talking in the order of two or three times more, if there is a signal, because in dry places there might not be an extreme rainfall signal, and similarly there is probably not going to be a signal of increasing drought frequency in really wet parts of the world.”

People should not be surprised, or cynical, when there are several ‘one-in-100-year events’ in a short period, he says.

“It sounds counter-intuitive but, actually, we shouldn’t be surprised by this clustering—there are certain pre-conditions, say in the tropical atmosphere, that set you up for a greater chance of having these bad weather events.

“Also, if your sea-surface temperatures around the country are warmer than normal, then that will generally increase the risk of these things being worse.”

Luke is now focusing on extreme heat in New Zealand.

“For a long time, we’ve assumed the impacts of extreme heat in New Zealand are basically zero. But extreme heat is the fastest-changing weather-related hazard under climate change, so it’s a risky bet to stick with that assumption over the next several decades.

“I’m also trying to understand how heatwaves and droughts in New Zealand might feed off one another, and what hidden risks might emerge over the next few decades, particularly in terms of heat stress in livestock, health risks for our rapidly ageing population, and perhaps even the risks of power cuts as our reliance on air conditioning in the summer continues to grow.”