How “dirty” is the 2023 election campaign so far? And what’s happened to “relentlessly positive” campaigning in the post-Ardern era?

Two weeks into the 2023 New Zealand Social Media Study, 1,554 Facebook posts by political parties and their leaders have been analysed by Dr Mona Krewel, director of the Internet, Social Media and Politics Research Lab (ISPRL) at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington, and her team. The posts were made in the period from 11 to 24 September.

Accentuating the negative

Early in this election campaign, National and Labour were accusing each other of going ‘negative’, Dr Krewel says.

“National argued Labour was running ‘the most negative campaign in history’. Labour countered National was ‘thin-skinned’ but in turn complained about a number of attack ads from the National Party.

“This is a very strategic move. They accuse each other of running a negative campaign and draw attention to negative comments made by their opponent, in the hope that voters will take a dim view of such comments and the party that’s making them.”

So, what do the parties’ Facebook posts reveal about whether they’re running negative campaigns?

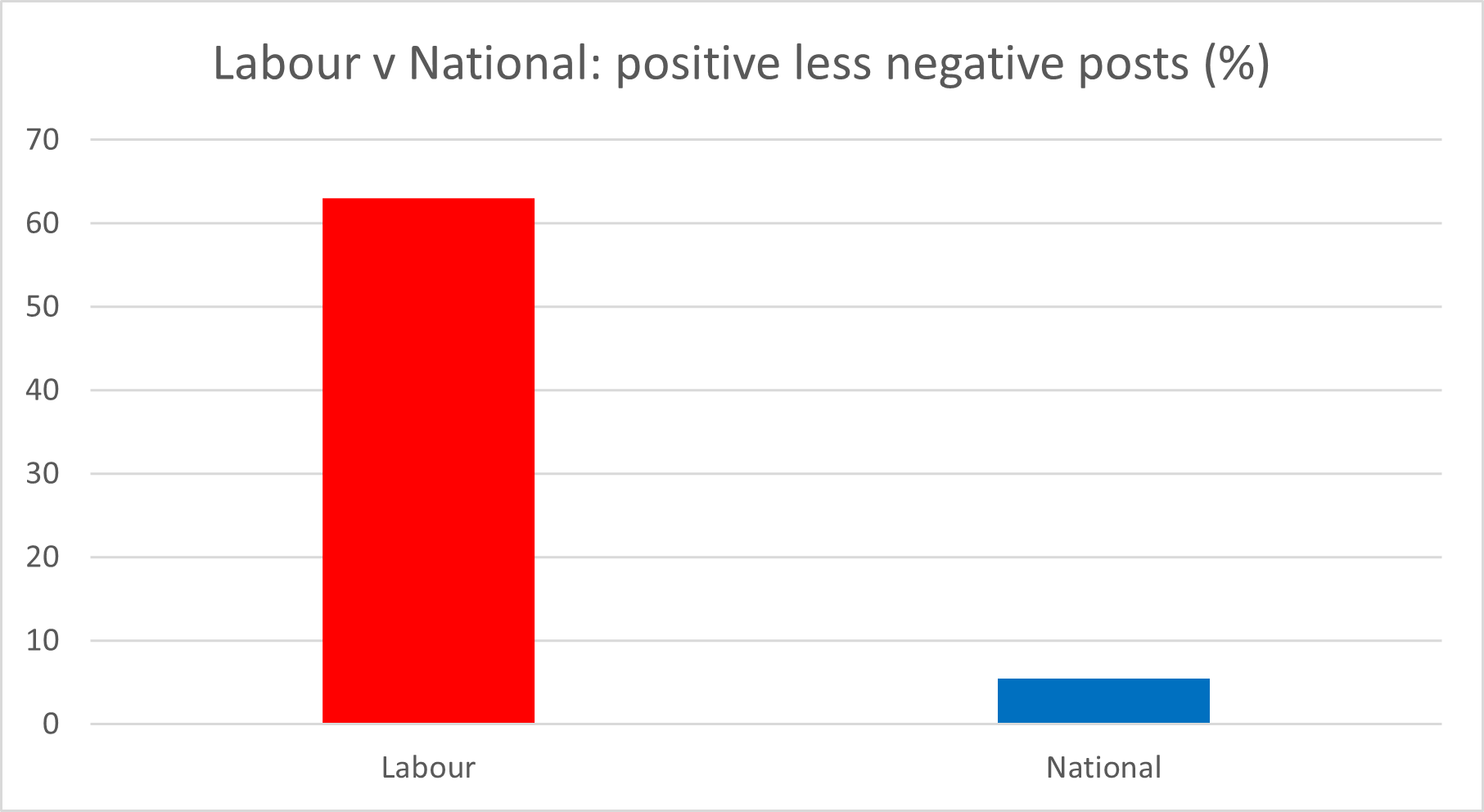

“Results show National is far more negative than Labour, which is campaigning from an incumbent’s position and that means mostly staying positive and trying to emphasise achievements in government.

“If we subtract negative posts from positive posts, about 63 percent more Labour posts included positive self-presentation than negative attacks. In comparison, when we do the same for National, it had a net positivity score of just 5.5 percent.”[1]

Dr Krewel says negative campaigning is not automatically a bad thing and many researchers argue there’s a “positive case” to be made for negative campaigning.

“Criticising a government, or pointing out public mismanagement, and providing voters with electoral alternatives are key functions of democratic campaigning and may help voters to make informed voting decisions.”

In other words, it’s part of the job description when you run a campaign.

“This is especially the case for National as the challenger party. Labour, as the incumbent, will mostly have to defend its record and ask voters for three more years by pointing out its achievements.”

There are also more incentives for challenger parties to go negative—in particular, because negative content not only increases voters’ attention but also journalists’ attention, she says.

“Negative content has a higher news value than positive content and therefore gets picked up more often by mainstream media. And challenger parties have to fight harder for the media’s attention than incumbents.

“Plenty of studies have confirmed a so-called incumbency bonus for governing parties and acting prime ministers when it comes to the visibility of parties and candidates in the media. Challenger parties therefore usually seek the media’s attention by going negative.”

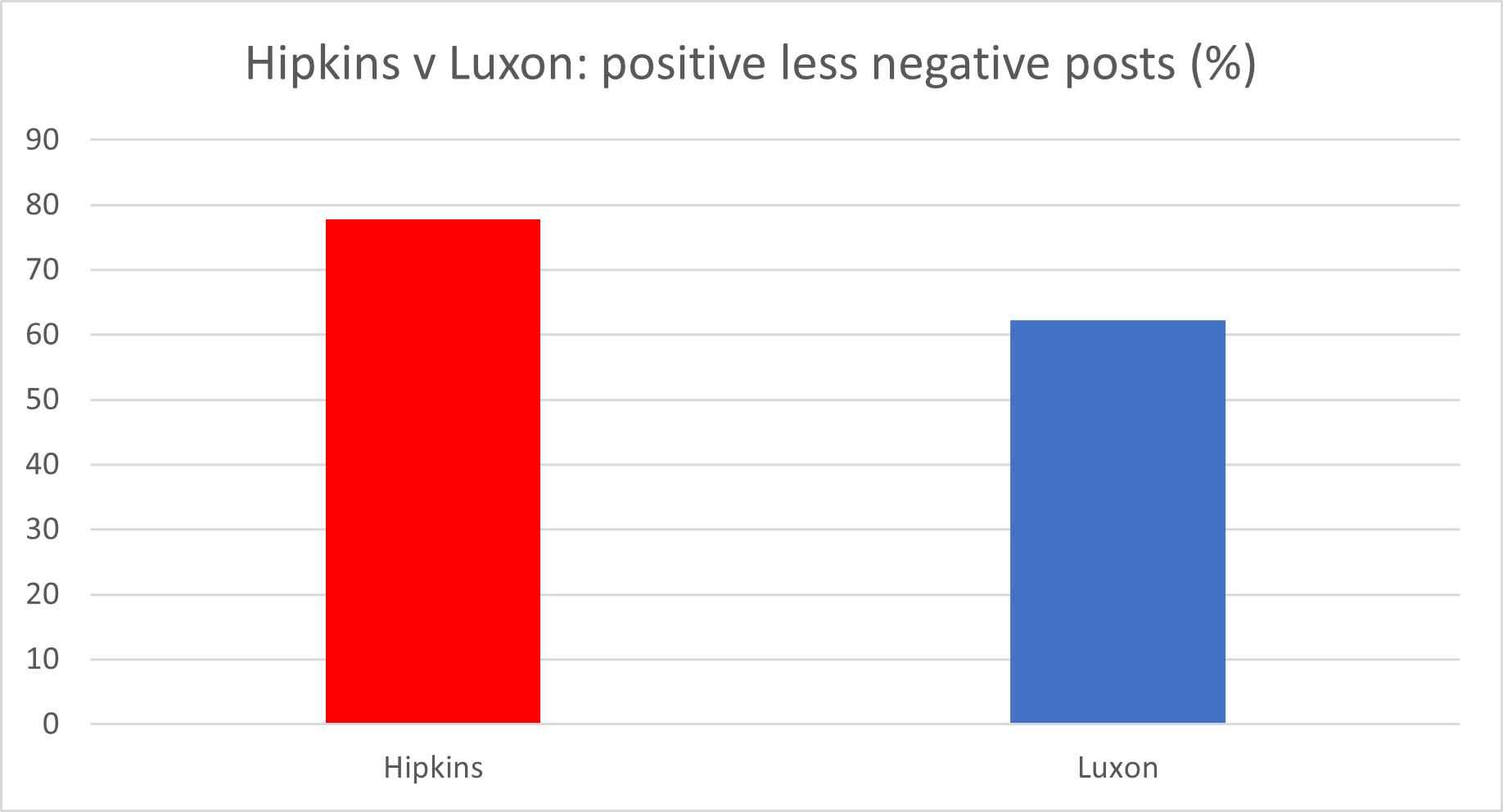

The picture was similar when the researchers looked at Facebook posts by Prime Minister Chris Hipkins and National Party leader Christopher Luxon.

“As the opposition leader, Luxon attacks more frequently than Hipkins, though the difference is less pronounced than in posts by their parties. There is a clear division of tasks in the case of National here: Luxon leaves it to his party to attack and does so less frequently himself.”

Similar trends have been observed in other countries.

“Studies in the US and Europe have found high-profile party members, such as party leaders or cabinet ministers, attack less and leave this to their parties. In the US, parties often outsource the fiercest attacks to ‘political action committees’ and candidates refrain from too much negative campaigning to avoid any potential backlash.”

Negative campaigning doesn’t necessarily put off voters, Dr Krewel says.

“For a long time, political communication scholars believed in the so-called ‘demobilisation hypothesis’, which holds that voters get turned off by negative campaigning and therefore stay home and don’t vote.”

However, research on the ‘demobilisation hypothesis’ is inconclusive. Recent meta-analyses of studies haven’t been able to confirm that negative campaigning lowers voter turnout, she says.

“Whether negative content has ‘mobilising’ or ‘demobilising’ effects depends on a number of factors. US research has found turnout increases as long as the volume of negative ads equals that of positive ads. But when negative ads exceed the positive, the positive effect on turnout decreases and there may even be a drop in turnout.

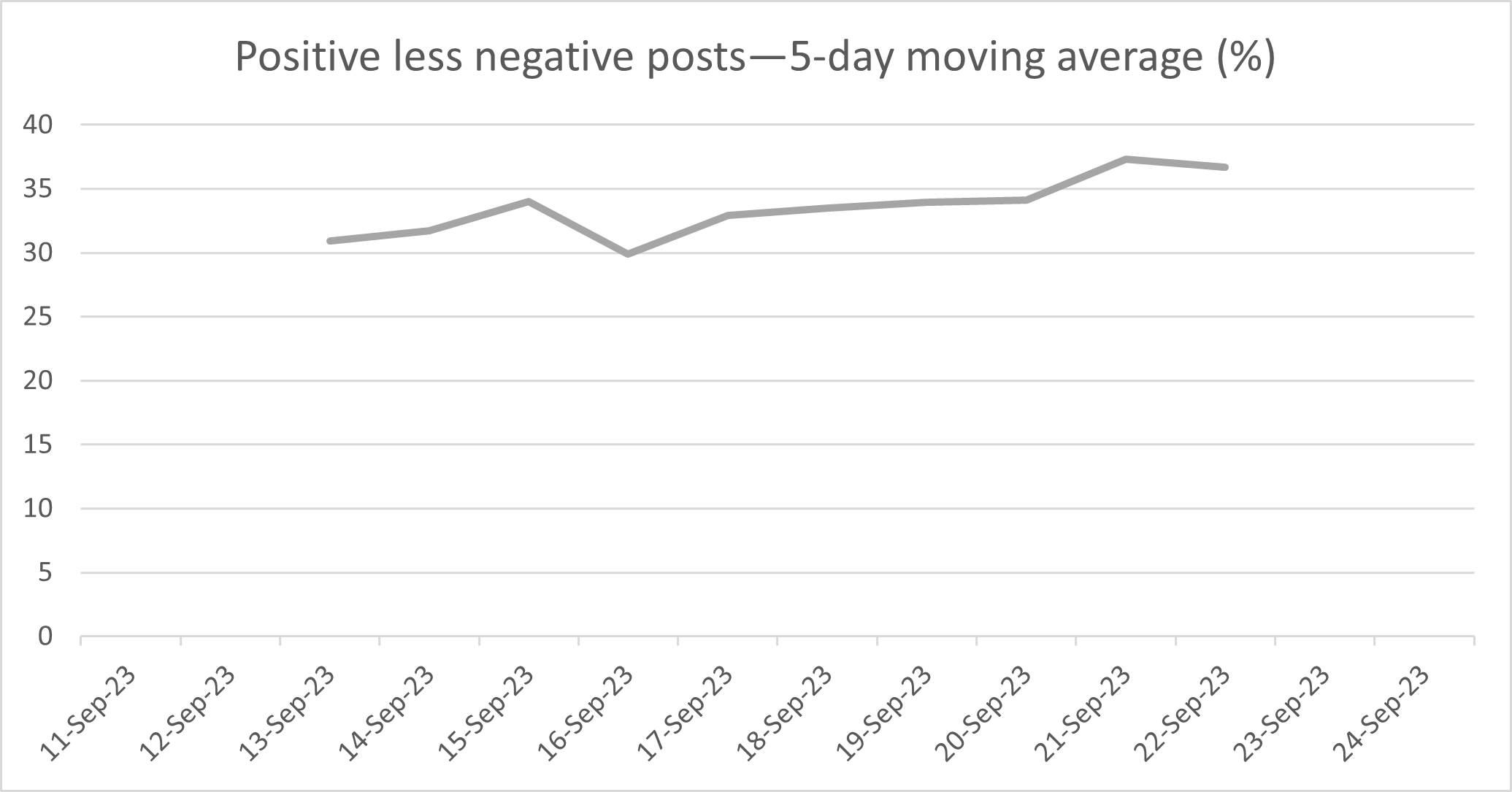

“If we look at the ratio of positive to negative posts across all parties in our sample in the past two weeks, the positive content still outweighs the negative content. The smaller, parties, which are often more negative, slightly drag down the positive campaign trend.”

The graph below shows the five-day moving average of positive less negative posts. A five-day moving average has been used to smooth out short-term fluctuations and highlight the trend of the campaign period.

Who are the targets of negative campaigning?

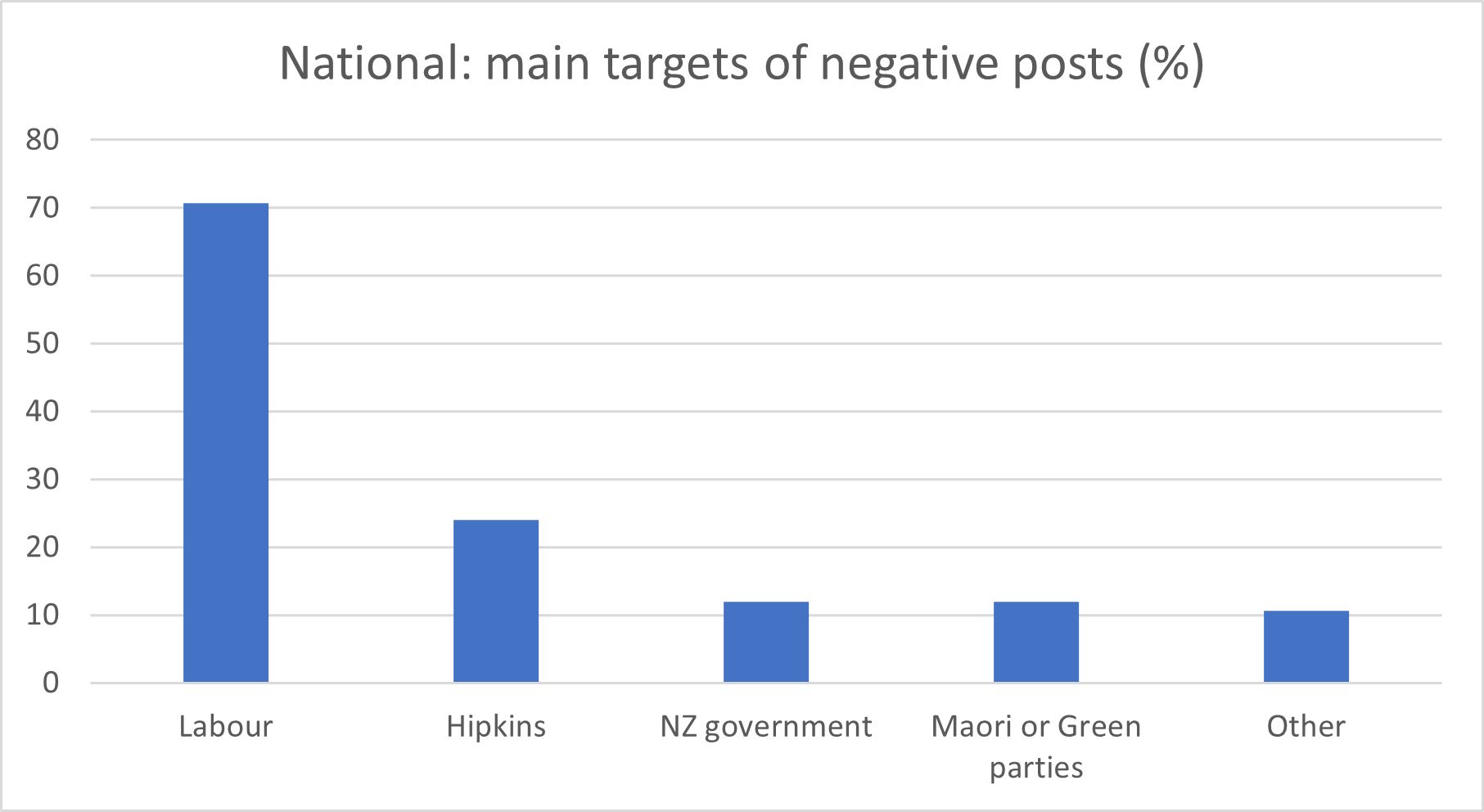

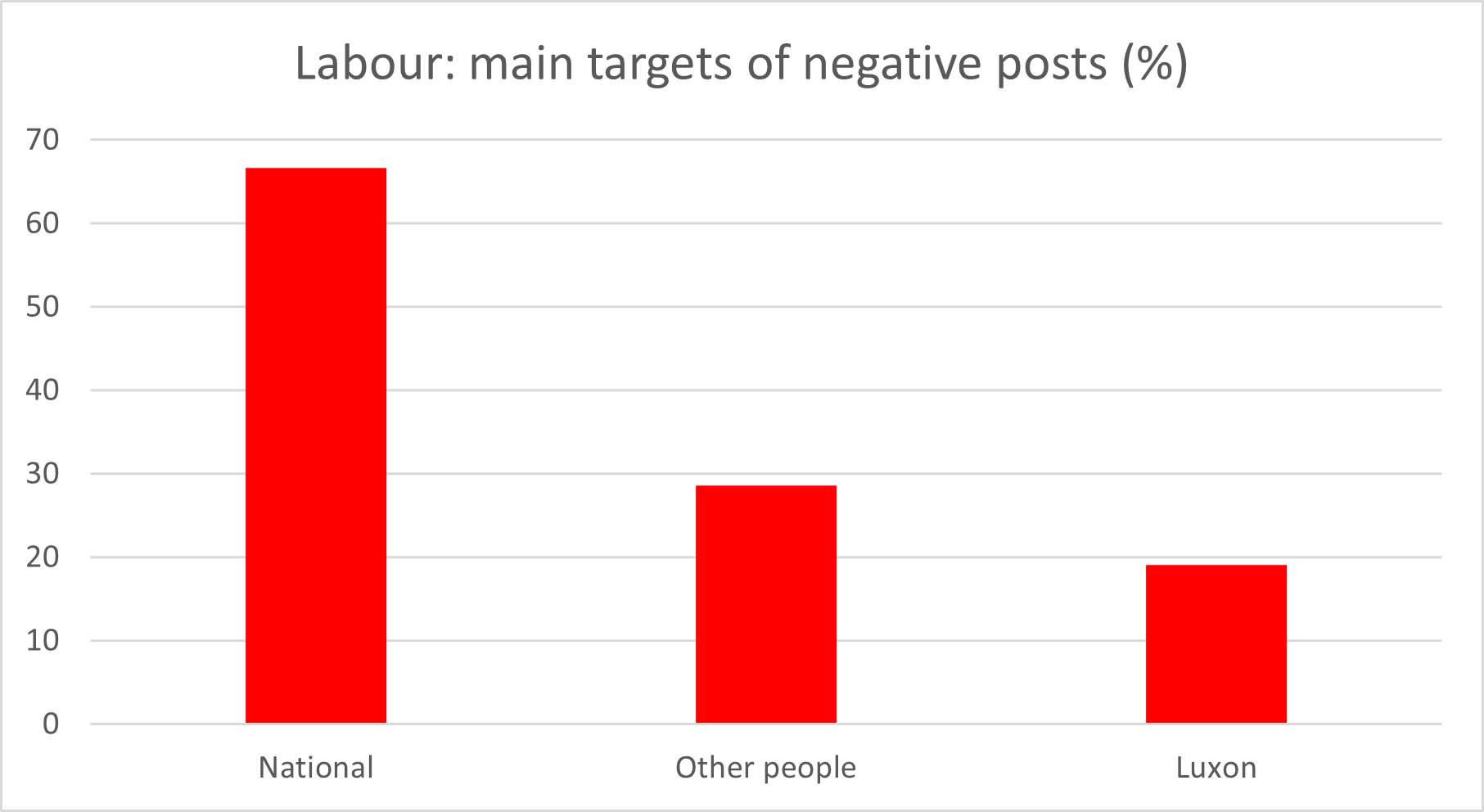

Not surprisingly, results show the main targets of National’s negative posts are Labour and PM Chris Hipkins, the government in general, and Labour’s potential coalition partners, Dr Krewel says.

“Labour’s attacks, on the other hand, are less clearly focused. While they attack the National Party and Luxon, some (six posts) also attack other people.

“Based on these results, it is pretty difficult to back up National’s claim that Luxon has been the centre of very personalised attacks by Labour. There might have been some harsh attacks. However, in terms of the quantity of posts, Hipkins and Labour have had to take far more hits from National than the other way around.”

It’s the economy, stupid

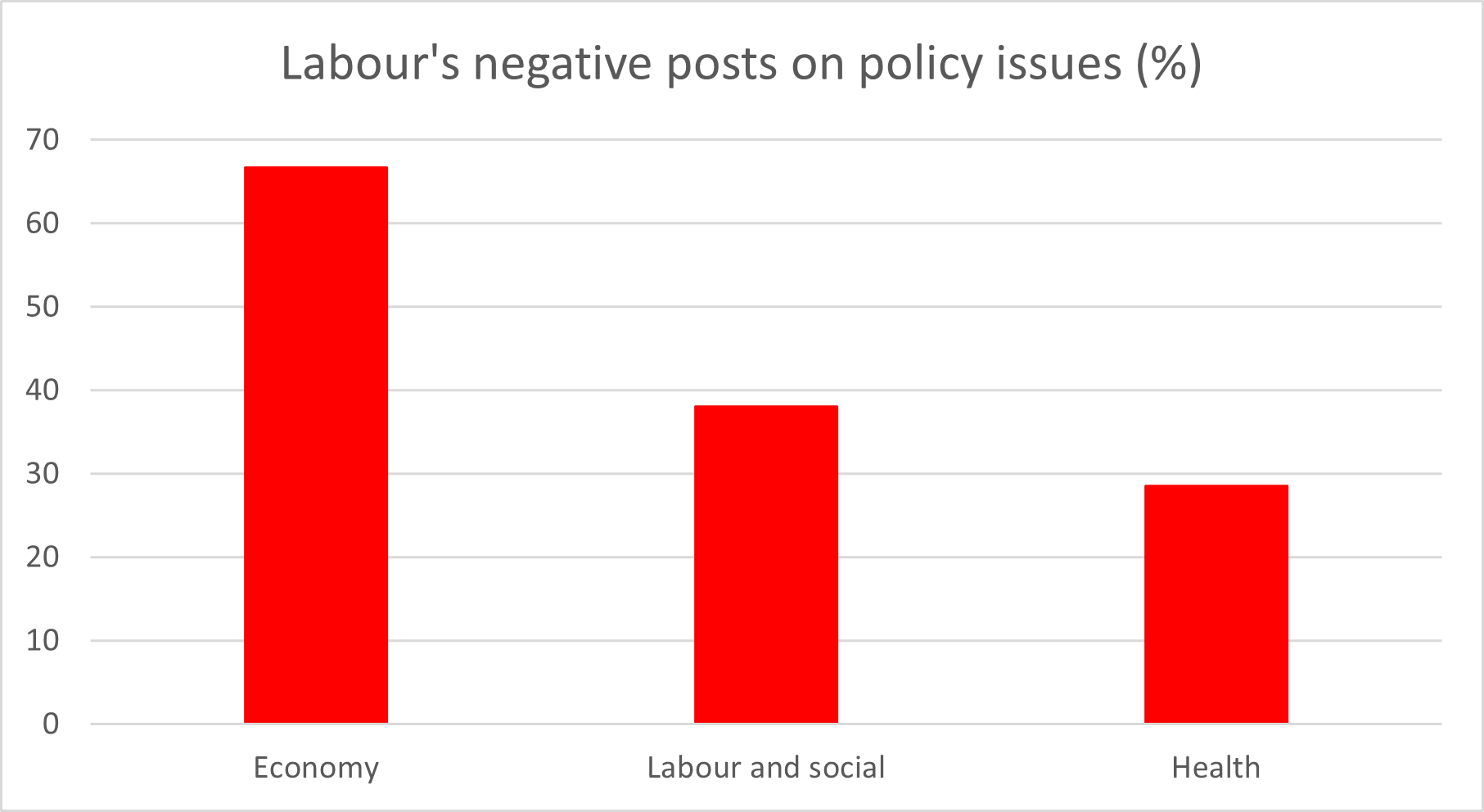

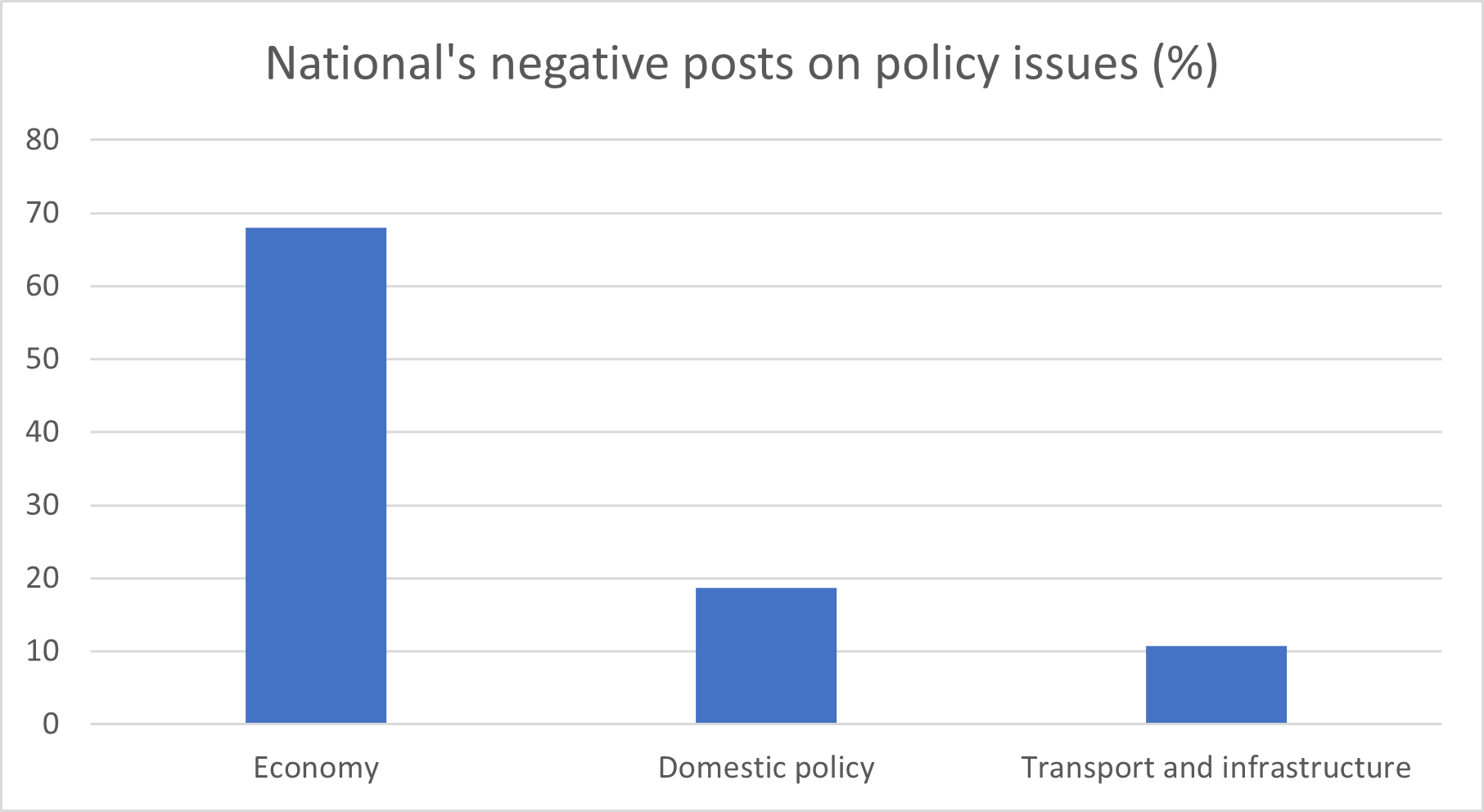

The economy is the key battleground of this election and of the two main parties’ social media campaigns, says Dr Krewel.

Both Labour and National have published more negative Facebook posts attacking each other on economic policy than on any other issue.

“The reason why they mostly attack each other on economic issues is that the economy is usually ranked as either the most important topic or at least as one of the most important political topics in the eyes of voters,“ Dr Krewel says.

“It makes sense for National to go negative here. Challenger parties always try to hammer home the ‘economy is in bad shape’ message and that it’s the government’s fault. The cost of living crisis also makes it easy for National to attack Labour on the state of the economy.

“Both National and Labour also try to attack in areas where they are usually seen as competent by voters. National is perceived as stronger on economic and domestic policies while Labour is seen as stronger on labour, social and health policies.

“In political science, we call this ‘issue ownership theory’. Certain issues are ‘owned’ by certain parties and parties like to attack on topics where they believe they have a competence advantage.

“Parties will attack on topics where they’re convinced their own record is good but their opponent’s record is not. This makes it harder for their competitors to counter the attacks and for voters to doubt them.”

Has ‘be kind’ become ‘be nasty’?

Overall, social media campaigning this election appears to be far less negative than the campaign outside of social media, Dr Krewel says.

“From what we’re seeing on the campaign trail, you get the impression we are dealing with a pretty rough campaign this time. Election billboards are being vandalised. Labour candidate Angela Roberts got slapped in the face at a local election debate. Te Pāti Māori candidate Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clark reported break-ins at her home and an intruder leaving a threating message.”

However, on social media, positive campaigning currently still outweighs negative campaigning, she says.

“Both big parties do their job. Labour defends its record and chooses a campaign of positive self-presentation over negative campaigning, which makes sense for a governing party. National, as the challenger party, runs a fierce attack campaign, which is what most challenger parties do.

“Both parties try to attack in areas that are either salient on the campaign agenda and therefore cannot be avoided, such as the economy, or where they have a strategic advantage over their opponent in terms of issue ownership,” Dr Krewel says.

Note

[1] A post could include both negative and positive statements or neither (neutral). A post contained negative campaigning when it aimed at critically presenting the political opponent. This involves all forms of attack on the political opponent (party, politician, coalition, institution). Negative campaigning criticises socially relevant topics, uses stereotypical traits, highlights shortcomings as well as criticises and attacks qualities and behaviour of parties, politicians, and related issues. Exaggerations and evoking negative emotions such as fear, envy, blame, and anger are also considered as negative campaigning. Coders were advised to code that a post contains positive campaigning when it included positive statements, pictures, and emotions that were of a supporting, encouraging, affirmative, beneficial, or assertive nature and presented the advantages of a party’s own candidate, their goals, and competencies. A neutral post was coded for neither negative nor positive campaigning.