Which party is posting the most on social media in the final stretch of the election campaign? What are they posting about? And are we really seeing the rapid rise of mis- and disinformation in Aotearoa that some have been expecting in this election?

In the first week of 2023 New Zealand Social Media Study, 681 Facebook posts by political parties and their leaders have been analysed by Dr Mona Krewel, director of the Internet, Social Media and Politics Research Lab (ISPRL) at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington, and her team. The posts were made in the week of 11 to 17 September.

“The number of posts from our first week of data collection is of course still small. However, the data already gives us a good indication of the effort parties are putting into their social media campaigns. Over the coming weeks, we’ll get a much clearer picture of how the candidates and parties are campaigning after we have analysed more posts and our data set has grown,” Dr Krewel says.

Parties covered by the study are:

- the five parties currently in parliament—Labour, National, the Green Party, ACT, and Te Pāti Māori

- eight parties outside parliament—Freedoms New Zealand, the Leighton Baker Party, New Nation Party, New Zealand First, New Zealand Loyal, NZ Outdoors & Freedom Party, The Opportunities Party (TOP), and Vision New Zealand.

The Facebook page of each party leader is also included in the study if the leader has an active page.[1]

So, who’s posting and how much?

Compared with 2020, results show most parliamentary parties appear to have delayed the start of their social media campaigns.

“This year, we see fewer posts from the parties than we saw in the corresponding period leading up the 2020 election. The exception is ACT, which is relying heavily on social media and is very active on Facebook at this point of the campaign. The party posted nearly three times as much as it did in the first week of the 2020 campaign.

“Most of these posts are in fact posts by the party leader David Seymour and not by the party. Apparently, Seymour aims at becoming New Zealand’s new social media powerhouse in the post-Ardern era," Dr Krewel says.

The lower number of social media activities from the other parties may reflect the comeback of door-to-door canvassing and other traditional ‘in-person’ campaign events.

“While direct in-person campaign activities were still possible in New Zealand in 2020, most parties probably planned them more cautiously and allocated higher budgets to their social media activities as COVID-19 disruptions were always a possibility.

“This year, they’re able to get back to knocking on doors and other ‘traditional’ campaigning, which likely means a less intense focus on social media than in 2020. However, I expect all parties will gear up their social media activities and we will see posts increase soon.”

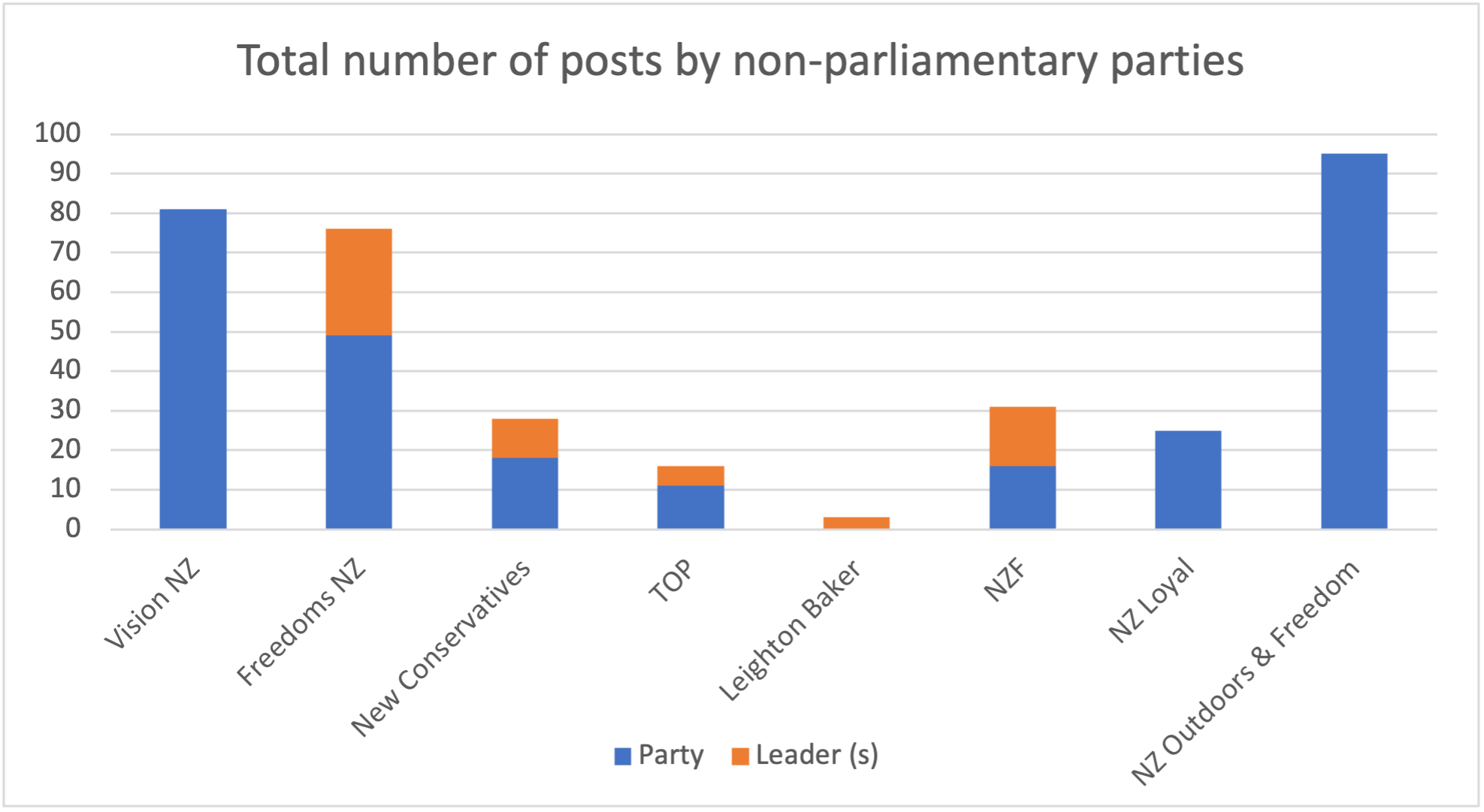

Across all parties in the study, a disproportionally high number of posts were from the NZ Outdoors & Freedom Party in stark contrast to their performance in the polls, Dr Krewel says.

“This shows you can’t make any interferences from a party’s social media activities about their potential electoral success. Smaller parties and, in particular, fringe parties such as the NZ Outdoors & Freedom Party and Vision New Zealand are often very active on social media, as this campaigning is cheap and they lack the financial resources of the bigger players.

“They also get much less media coverage given their political insignificance, which means they are more dependent on social media to get their messages out.”

Dr Krewel says posts from these parties are usually far less professional than those of the parliamentary parties and cater to small audiences, “often audiences with extreme political perceptions and attitudes and which solely rely on social media for their political information because they distrust the so-called mainstream media.

“NZ Outdoors & Freedom only has 30,000 Facebook followers so despite the high volume of posts, not many people are actually reached by the party’s political messages. That compares with the National Party, which has about 155,000 Facebook followers, and the Labour Party, which has 307,000.”

Campaign topics

The topics of the parties’ social media posts are much the same as in 2020.

“Results this year are not much of a surprise. It looks like the parties are focusing on the same topics as always with the economy being the most important followed by labour and social issues.

“This is to be expected, given the economy is always the most important topic for parties and usually one of voters’ highest ranked priorities in the majority of election campaigns around the world. In the middle of a cost of living crisis, in which parties try to convince voters they have the recipe to fix this problem, we wouldn’t expect to see it change.”

Facts and fiction

What about the quality of the parties’ social media communication in this election so far? Are we seeing mis- and disinformation increasing compared with 2020?

Dr Krewel says the 2020 election happened before the COVID-19 vaccine rollout and the political landscape then was far less polarised than it is today.

She also points out that in both the 2017 and 2020 elections, Jacinda Ardern promised New Zealanders they would see an honest and relentlessly positive campaign from her and the Labour Party, a promise which was echoed by the Green Party.

“We have heard no such promises from any party ahead of this election. It would therefore not be unexpected to see an erosion of the high campaign standards for which New Zealand election campaigns have been known. Very early on in the campaign, we also saw parties accusing each other of making false claims.

“However, so far it seems most parties are upholding the standards of high-quality political discourse. We did not find any fake news [2] posts from any of the parliamentary parties in the first week of monitoring. We can only hope it stays like this until election day to help New Zealanders make informed voting decisions.”

However, it was a different story for parties outside parliament.

“Although the majority did not post any fake news in the first week of our study, the parties under the umbrella of the Freedoms New Zealand coalition stand out and not in a good way. These parties include NZ Outdoors & Freedom and Vision New Zealand,” Dr Krewel says.

“Nearly 11 percent of Facebook posts from the NZ Outdoors & Freedom party contained false claims, the highest we saw. This is not surprising given party co-leader Sue Grey this week raised the ‘litter boxes in schools’ hoax at a candidates meeting.”

The hoax alleges that schools provide litter boxes for students who identify as cats or furries.

“It’s a myth that has been debunked many times and simply has the goal of attacking transgender communities.”

Dr Krewel says results so far show disinformation is limited to a small group of extreme fringe parties in Aotearoa.

“If we only look at fake news posts that qualify as full-fledged conspiracy theories, this doesn’t change.[3] Conspiracy theories are also solely associated with parties under the umbrella of the Freedoms coalition at the moment.

“When they explicitly address certain groups and try to appeal to them, the preferred audience is made up of anti-vaxxers, the former ‘freedom convoy’ protesters, and extremely conservative voters.

“This means the voter segment they are targeting is usually a right-wing, vaccine sceptical, and often socially conservative audience. The anti-mandate protests at parliament last year were the peak for this movement and it makes sense that it tries to appeal to these crowds again to get them to turn out. However, polls show they have had limited success.”

Half-truths and innuendo

The picture changed slightly when the researchers investigated Facebook posts that contained half-truths.

“Very often a Facebook post is not entirely false and not completely made up. Often, most of the information presented is accurate apart from one small detail. This we call a half-truth, as it would be exaggerated to speak of fake news in these cases. It’s a form of ‘fake news light’.

“Unsurprisingly, we often find these half-truths also among posts by the established parties. This is nothing new and we have seen political parties slightly bend the truth in all elections and across the political spectrum from left to right.”

In the first week of monitoring, researchers spotted half-truths in social media posts by the National Party and ACT and in David Seymour’s and Christopher Luxon’s social media communication, Dr Krewel says.

“In the case of Seymour, such half-truths appear in six percent of his Facebook posts—four posts in total. In Luxon’s case, one post contained a half-truth.”

Dr Krewel gives an example of a post by the National Party that stated, “The Ministry of Pacific Peoples spent almost $53,000 on four Budget 2023 breakfast events promoting Labour MPs at a cost of $76 per person who attended”.

She says, "while it’s correct the ministry hosted the events, and the amount spent on them is also correct, the breakfasts' purpose was not to promote Labour MPs as claimed. They were advertised as 'an opportunity for our stakeholders and communities to talanoa with ministry staff and government officials following this year's Budget 2023 announcement'. There is no indication these events were promoting Labour MPs”.

However, the number of half-truths in posts by parliamentary parties is relatively low when compared with posts by non-parliamentary parties, Dr Krewel says.

“It’s not just parties in the Freedoms coalition but also parties such as New Zealand First and the New Conservatives using half-truths. And Winston Peters’ social media communication also contained two half-truths, though fewer than ACT’s. It seems he is trying to win over voters who have no trust in the established parties but who don’t want to waste their vote as none of their preferred smaller parties will come anywhere near to getting elected."

Dr Krewel says she is cautiously optimistic this won’t be a dirty election campaign.

“We are just one week into the final campaign phase, but what we see overall makes me slightly optimistic about the quality of this election campaign. The mis- and disinformation level is not high and seems largely limited to a group of minor parties and their leaders who neither have much outreach nor success in the polls. But we will be monitoring closely how things develop from here.”

The New Zealand Social Media Study will continue to monitor Facebook posts until election day on 14 October.

Notes

[1] For Vision New Zealand, no leader is included in the sample as party leader Hannah Tamaki only posts about private matters on her personal page. For the New Nation Party, no leader is included as party leader Michael Jacomb’s Facebook page is not public. For the Leighton Baker Party, only Leighton Baker’s personal page is included as his party does not have its own Facebook page.

[2] Fake news, for the purpose of this study, in accordance with most academic literature on disinformation has been defined as completely or for the most part made up and intentionally and verifiably false posts to mislead citizen. The usual disagreements and accusations between political actors have not been coded as fake news. Coders were advised to fact-check each post carefully using reliable sources. In case of doubt or when they could not find unquestionable contrary information, they were advised to code the absence of fake news. The term fake news remained reserved for very clear and severe cases only. In acknowledgement of everyone’s right to freedom of speech, the project intentionally chooses to under- rather than overestimate the amount of disinformation on social media.

[3] Conspiracy theories, for the purpose of this study, have been defined as an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable. It is typical for a conspiracy theory to be based on prejudice or insufficient evidence. A conspiracy theory is usually in opposition to the mainstream consensus in a society, as advocated by scientists or other academics who are qualified to evaluate its accuracy.