Researchers from Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington, the Universidad de Chile and Meteorológica de Chile, discovered the existence of ‘The Blob’, which they believe is generated by recent climate change, and found it has a significant influence on the climate of the Southern Hemisphere.

Their paper 'The South Pacific Pressure Trend Dipole and the Southern Blob' has been published in the Journal of Climate this week. The research shows that the area of intense warming in the South Pacific Ocean has shifted storm systems towards Antarctica and away from the west coast of South America, causing a decade-long, uninterrupted sequence of drought years across central Chile and adjacent portions of the Andes Mountains and Argentina. It has been termed the ‘Central Chile Megadrought’, given its unprecedented longevity.

Co-author Dr Kyle Clem, a Lecturer in Te Kura Tātai Aro Whenua—School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences, says it is unclear when ‘The Blob’ will dissipate, given it has formed as a result of human-induced climate change.

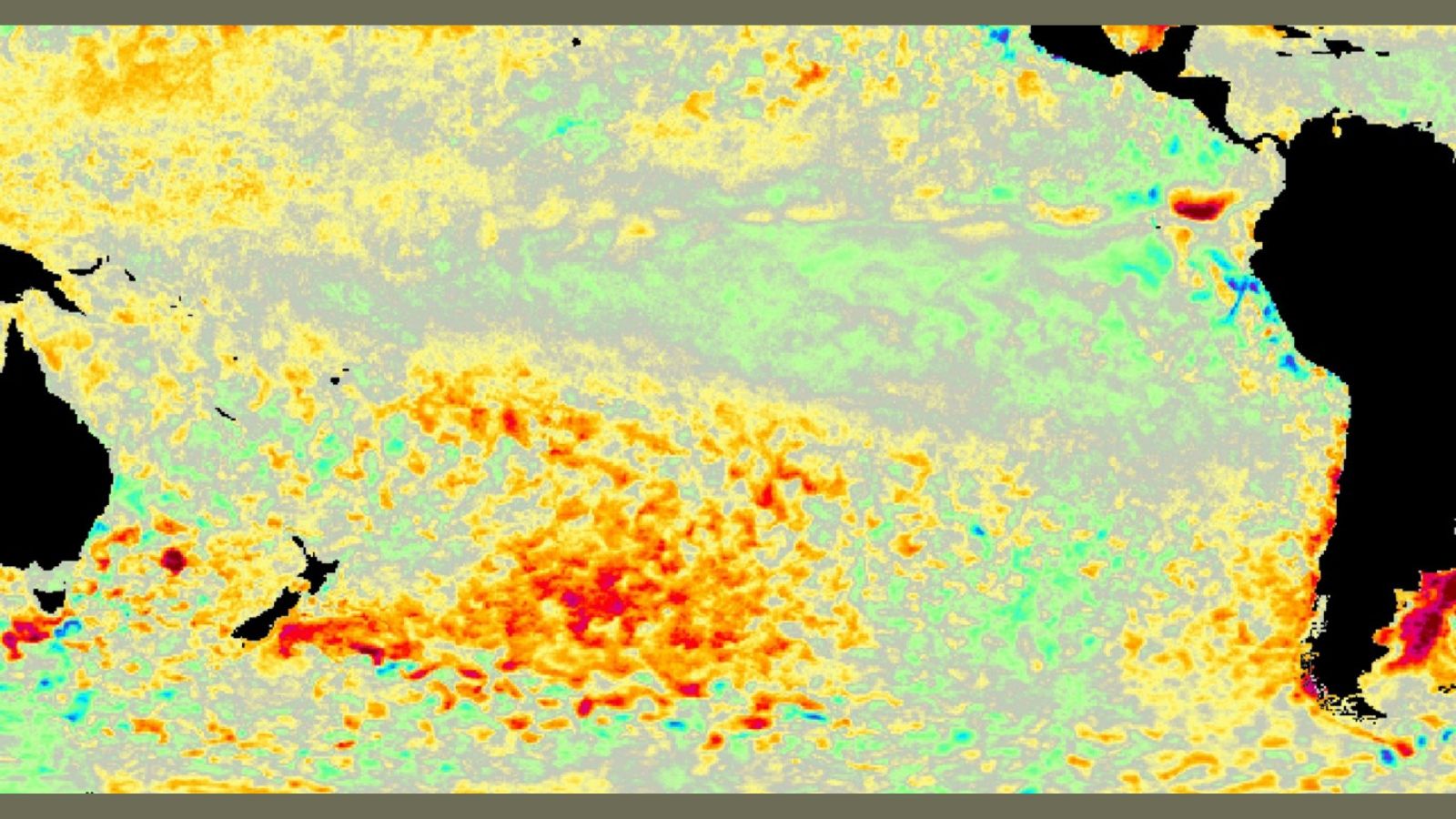

The discovery of ‘The Blob’, covering an area about the size of Australia (approximately 8 million sq km), came about from studying year after year of drought conditions in central South America and investigating the strong, continuous warming of upstream ocean waters in the South Pacific.

“With an uninterrupted sequence of dry years across central Chile—home to more than 10 million inhabitants—since 2010, scientists in South America sought answers,” Dr Clem says.

“It was clear that winter storm systems, which deliver the majority of annual rainfall in this Mediterranean climate, were moving south toward Antarctica and being replaced with a large ridge of warm and dry high pressure extending from New Zealand to the central South American coast.

“Further investigation revealed the ridge of high pressure was rooted in a large region of rapid ocean-warming east of New Zealand. This fuelled our current investigation of the role of this blob of ocean warming in driving the atmospheric circulation changes affecting the southwest Pacific region.”

Dr Clem says the world’s oceans have absorbed about 90 percent of the heat gained by Earth from increasing greenhouse gases.

The global average rise in sea-surface temperature (SST) is about 0.5°C in the past 40 years (1979-2018), but that is not evenly distributed across the oceans.

“In our study, we found this blob of intensely warming sea-surface temperatures has warmed about three times faster than the global average, by 1.5°C over the same period, during the May – September winter season.

“This blob of extreme warming reaches depths of about 100 metres. Despite covering only around 1 percent of the total global ocean surface, a recent study suggests ‘The Blob’ accounts for as much as a quarter of the total global ocean heat absorption in recent decades,” he says.

The development of ‘The Blob’ appears linked to a decline in convective rainfall over the central tropical Pacific in recent decades, explains Dr Clem. That decline triggers a change in regional atmospheric circulation east of New Zealand that favours warm water to travel into ‘The Blob’ and reduces the upwelling of colder water from depth.

Computer models, which do not account for anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, manage to replicate ‘The Blob’ and show a connection to a decline in convection in the central tropical Pacific.

“The extreme rate at which ‘The Blob’ has been warming over the past 40 years far exceeds any rate that could occur under natural variability alone. So while ‘The Blob’s’ formation may have been triggered by natural processes, greenhouse gases have significantly contributed to the remarkable rate of warming and heat uptake in recent decades,” says Dr Clem.

The strong ridge of high pressure across the South Pacific built by ‘The Blob’ has blocked winter storms from reaching the subtropical west coast of South America, a region that relies on these storms to replenish freshwater sources before the summer dry season.

“In some years, rainfall has been as low as 30 percent of normal. This megadrought has dwindled freshwater supplies across central Chile, affecting drinking water in rural communities, hydro-generation, agriculture, and many other activities in a highly populated area that includes the capital city of Santiago.

“When I visited Santiago in late August 2019, at the end of the wet season, the famous snowy caps of the Andes Mountains were bare and the rivers that normally flow through the city were bone dry,” Dr Clem says.

It is unclear when or if ‘The Blob’ will dissipate and break the Chilean drought, with rainfall figures showing 2021 will be another very dry year.

“What our study shows is that, with human-induced climate change, what happens in one place does not necessarily stay there. The Southern Blob, though likely natural in its formation, has reached extreme levels of warming due to increasing greenhouse gases, with cascading effects on the climate system across the Southern Hemisphere affecting millions of people seemingly far-removed geographically from the source,” Dr Clem says.