The study, published in Nature Climate Change, is only the second to directly and formally link glacier melt to climate change, says lead author Dr Lauren Vargo.

“This is important, because having multiple studies in agreement means we can be even more confident that there is a link between human activity and glacier melt. This confidence is especially important for documents like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports, which use findings like ours to aid and inform policy-makers on climate change.”

The study also involved Dr Huw Horgan, Dr Ruzica Dadic, and Associate Professor Brian Anderson from the Antarctic Research Centre, Professor Andrew Mackintosh from Monash University, Dr Andrew King from the University of Melbourne, and Dr Andrew Lorrey from the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Science.

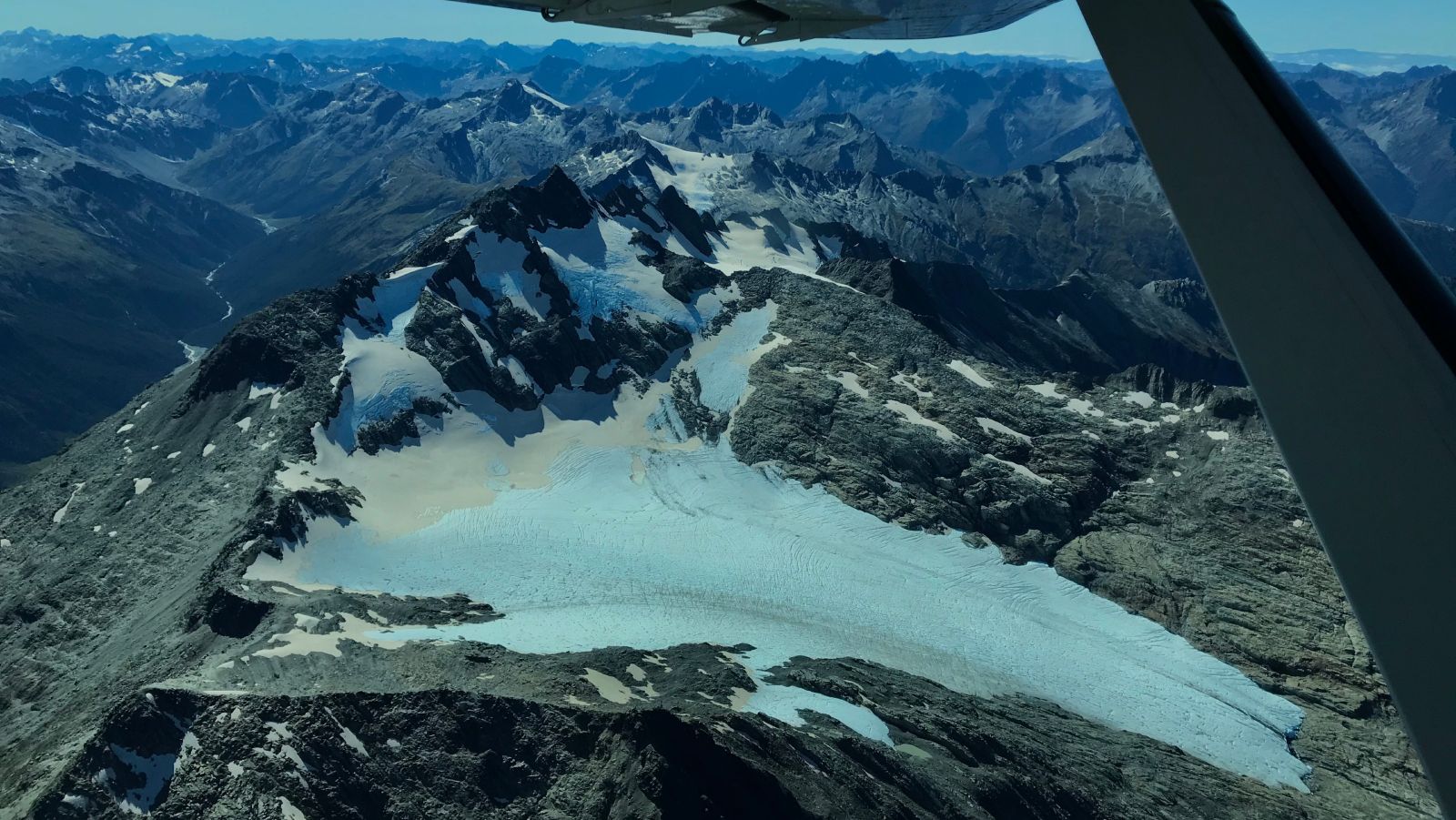

The study focused on a group of 10 glaciers in New Zealand’s South Island.

“It’s very likely that the extreme melt of these New Zealand glaciers was caused by human greenhouse gas emissions,” Dr Vargo says. “Specifically, our results show that high levels of melt in 2011 were six times more likely to have happened due to climate change, and high levels of melt in 2018 were at least 10 times more likely to have happened due to climate change.

“These increases in likelihood are due to temperatures that are 1 degree Celsius above pre-industrial levels, confirming a connection between greenhouse gas emissions and high annual ice loss.”

This study began in response to observations made during the 2018 End of Summer Snowline Survey, which Dr Vargo, other University researchers, and NIWA researchers collaborate on in March every year. The survey records the snowline position on New Zealand’s glaciers and ice geometry (thickness and flow) changes using aerial photos, which then allows researchers to determine the level of growth or shrinkage of key glaciers.

Dr Andrew Lorrey, who coordinates the annual Southern Alps snowline survey for NIWA, says. “This research shows one application of our work to monitor glaciers and reinforces the value of long-term snow and ice observations. The impacts from recent extreme years we’ve seen is concerning—the results from this study indicate human activities contribute to those years and load the dice against our glaciers.”

In 2018, the survey team observed the least amount of snow on the glaciers since the survey began, Dr Vargo says. They wanted to determine to what extent this lack of snow was due to human influence.

“We used a method called extreme event attribution, which is used to calculate the human influence on extreme climate events like heatwaves and droughts,” Dr Vargo says. “To get these results, we developed a framework that uses extreme event attribution together with calculating glacier mass changes with computer models.

“For example, the extreme loss of mass we saw of one glacier—the Rolleston glacier—in 2011 would be a 1 in 100 year event under natural conditions, but due to climate change this has become a 1 in 8 year event.

“Our results show that New Zealand glaciers are melting because of greenhouse gases emitted by humans,” Dr Vargo says. “Glaciers in New Zealand are important for many reasons, including tourism and water resources, so we hope that our findings will encourage and convince people around the world, but especially Kiwis, that we need to take stronger actions to stop climate change.”

Dr Vargo and her colleagues will now apply this method to studying more glaciers.

“There are over 100 glaciers globally that have annual measurements of mass change available, so we can use these with our new method to calculate the human fingerprint on glacier melt around the world.

“We know that many glaciers globally experienced their highest levels of melt in the last decade, so we look forward to investigating the link between this melt and human climate influence. Ultimately we hope this research can contribute to evidence-based decision making on climate change.”