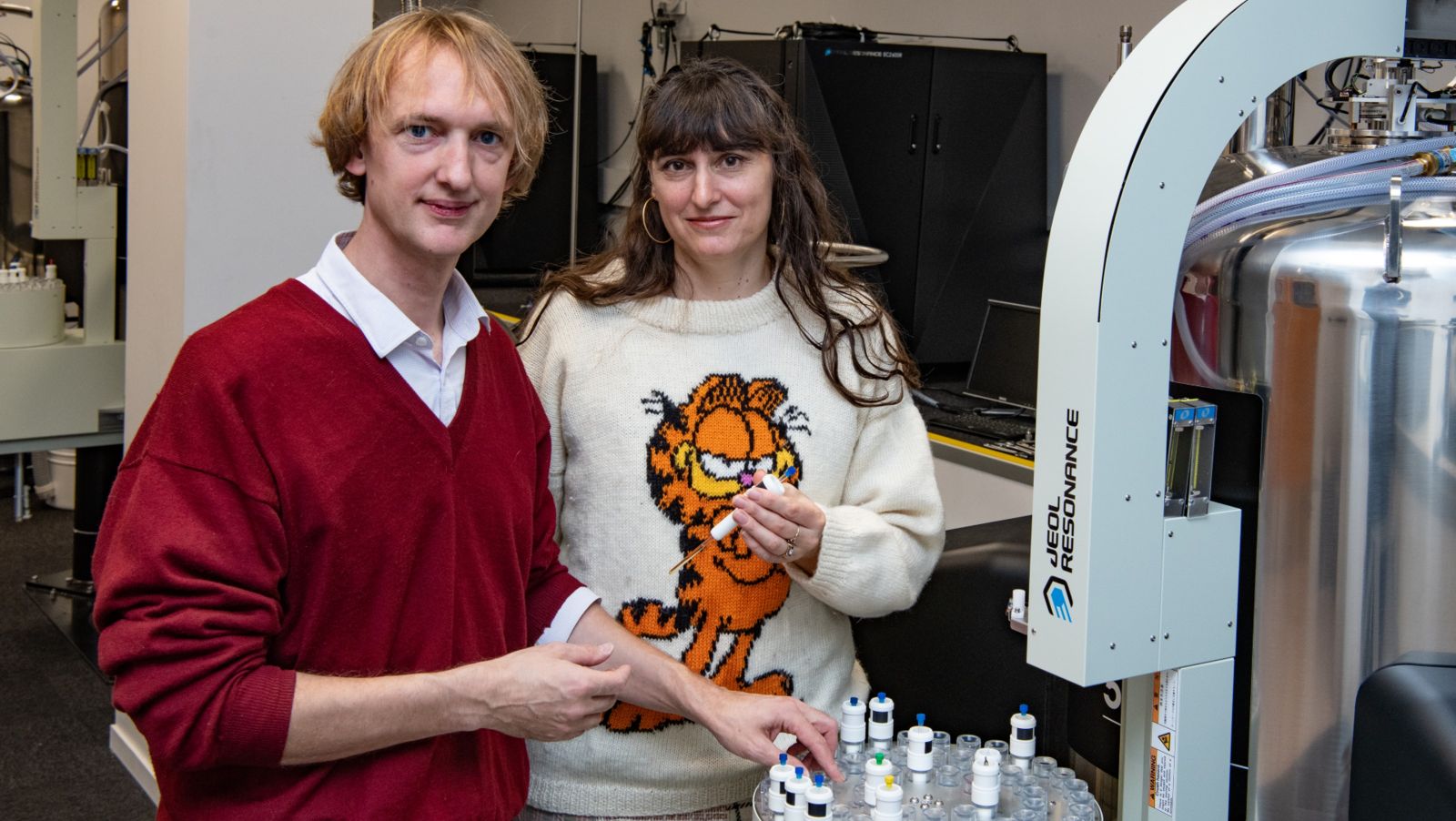

Today they work from a state-of-the-art laboratory on a number of exciting projects, including research to create better and more effective vaccines.

“When I first started as a student at Victoria University of Wellington, I had no idea what I wanted to do when I left university,” Associate Professor Stocker says. “But I enjoyed the practical aspect of lab work, and I distinctly remember the day when I held in a flask in my hand a new molecule that nobody in the world had ever made before. To me, that seemed really cool, and I liked the idea of making new things to help develop better therapeutics.”

Associate Professor Timmer was always interested in how bodies worked, but it was one of his father’s biochemistry books that sparked an interest in molecules, and how they can impact health and disease.

“I went to study chemistry at Leiden University in the Netherlands, and it was during this period I got really excited about organic chemistry and learned to make the molecules that are so important in health and disease,” Associate Professor Timmer says.

After completing their PhDs, both received prestigious scholarships to undertake postdoctoral positions at ETH Zurich, which is where they first met and became both co-researchers and a couple. After two years, they returned to New Zealand, with Associate Professor Stocker taking up a position at the Malaghan Institute of Medical Research and Associate Professor Timmer working for the University. Associate Professor Stocker joined the University in 2014.

“The beginning of my time at Malaghan was very much an ‘induction by fire’,” Associate Professor Stocker says. “I remember the director, Professor Graham Le Gros, walking me around the building and showing me magnified images of cells and asking what they were—I had no idea! In my mind, I thought that one looked like a flower!

“So that was how I learned about immunology—by osmosis and by picking up the odd textbook,” she says. “It just shows that you’re never too old to learn something new, and what you learn in your PhD doesn’t define you forever.”

Together they set up a research group focussing on the interplay between carbohydrates and the immune response.

“We were very fortunate to have several talented and motivated students join us early on, which set us up for success. This led to some excellent publications and research collaborations,” Associate Professor Timmer says. “We were also fortunate to receive Health Research Council and Marsden grants, which helped us set up a state-of-the-art laboratory.”

Associate Professor Stocker says working with students has been one of the biggest highlights of her career.

“While challenging at times, if I look back and think about what I’m most proud of it would be helping students achieve their goals,” she says. “One former student ended up with a fabulous job at a biotech company in San Francisco and was so happy he’d had such a great education with us that he wrote to us, thanking us, and explaining how he was teaching others science at the company.”

Another highlight was supporting her first PhD student back into work after the student had her children.

“I was able to fund her returning part-time and slowly upping her hours as she juggled her child care duties. The amount of work she achieved, and the quality of her work has been incredible. I’m a big fan of this type of model, giving researchers autonomy over how to best manage their time—everyone benefits from this.”

On a more personal level, Associate Professor Stocker says a big highlight for her was winning the Manhire prize forCreative Science Writing and the Easterfield Award in Chemistry in the same year.

“No one knew that I did some creative writing ‘on the side’, but no one was more shocked than I was when I won both awards,” she says. “It just shows it’s possible to do things other than science.”

On another creative note and a well-kept secret, Associate Professor Stocker designed the logo for the MacDiarmid Institute.

Associates Prof Stocker and Timmer have many strings to their bow including research on glycoproteins, solar cells, and ‘green’ chemistry, with their work on vaccine adjuvants being another successful endeavour. A vaccine adjuvant is a substance that is administered as part of a vaccine to enhance its effect.

“We have made great progress in the development of patented adjuvants that activate the immune cell receptor Mincle,” Associate Professor Stocker says. “This work has progressed into promising studies for a vaccine to help fight sheep pneumonia, and we hope that these studies will assist in the fight against pathogens that affect human health—this would be my ultimate research objective.”

This work has also led to an exciting collaboration with Professor Sho Yamasaki, an expert in this area from Osaka University in Japan, and through him Dr Kensuke Shibata from Yamaguchi University, who has helped the Associate Professors take great strides on another project of theirs.

Both Associate Professor Stocker and Associate Professor Timmer have some advice for aspiring researchers.

“Science is hard, so you should be really passionate about it to consider graduate research in the subject,” Associate Professor Stocker says. “But it’s such a great feeling when things work out, to be learning new things every day, and to be working on projects that can make society better.”

“From a practical perspective, you should give everything your best shot, and make sure both you and your supervisor are equally engaged—for a successful project, both sides of the team need to be fully committed to the task at hand.”

“Make sure you do what you want to do, or it will become very difficult,” Associate Professor Timmer says. “You have to work very hard and fail a lot of the time, so you need determination.

“That said, it is a great career path. Medicinal chemistry and immunology are at the centre of medications and preventative measures for public health. As we sit here waiting to see what will happen with COVID-19, it’s important to remember that a solid science background is crucial to understanding pathogens and diseases like this and finding ways to prevent or treat them. In that sense, being a scientist provides a tremendous opportunity to help society.

“Every discovery helps in some way, from a new vaccine adjuvant to a new mechanism that someone could use to develop a new drug. Every little bit counts. And even if you don’t end up becoming a researcher, a solid understanding of the scientific process will help you wherever you go.”