Young Ukrainian adults are prompting us to rethink what we mean when we talk about people having a ‘mother tongue’, as many are working to shift the primary language they use from Russian to Ukrainian amid the ongoing Ukrainian–Russian War.

Much research to date on the embodiment of language sees languages as a fixed part of a person, such that the language(s) they speak are seen as part of them, always tied to their identity.

However, for my new book, Choosing a Mother Tongue: The Politics of Language and Identity in Ukraine, I interviewed Ukrainians in their 20s and 30s actively working to change their mother tongue, suggesting we should look to a more fluid understanding of the term ‘mother tongue’ that better captures people’s lived experiences and complex, dynamic identities.

The 38 Ukrainians who took part in this research—who live in Ukraine itself or as part of the Ukrainian diaspora in New Zealand, the United States and Canada—show not all people feel language is a fixed part of themselves, but rather it is more appropriate to think of language as something that can be negotiated and renegotiated, in the same way we have come to regard identity.

As a member of the New Zealand Ukrainian community and a Ukrainian-American with Ukrainian heritage on my mother’s side, I am very familiar with how language, culture and politics are entwined in Ukraine. This has been so for many generations, always in complex and complicated ways.

By the fall of the Soviet Union, as a result of Russification, Ukraine had the largest Russian-speaking population outside Russia, and Russian remains the largest minority language in the country still today. However, since Ukrainian was declared the official state language in 1991, there has been a widespread increase in its use, albeit hugely varied, with Ukrainian dominant in Central and Western Ukraine but Russian still dominant in Eastern and Southern Ukraine.

The Ukrainian–Russian War following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and occupation of Eastern Ukraine in 2014 has further fuelled use of Ukrainian by many Ukrainians as a marker of aligning with a Ukrainian national identity (as opposed to a previously dominant focus on regional and/or ethnic identities).

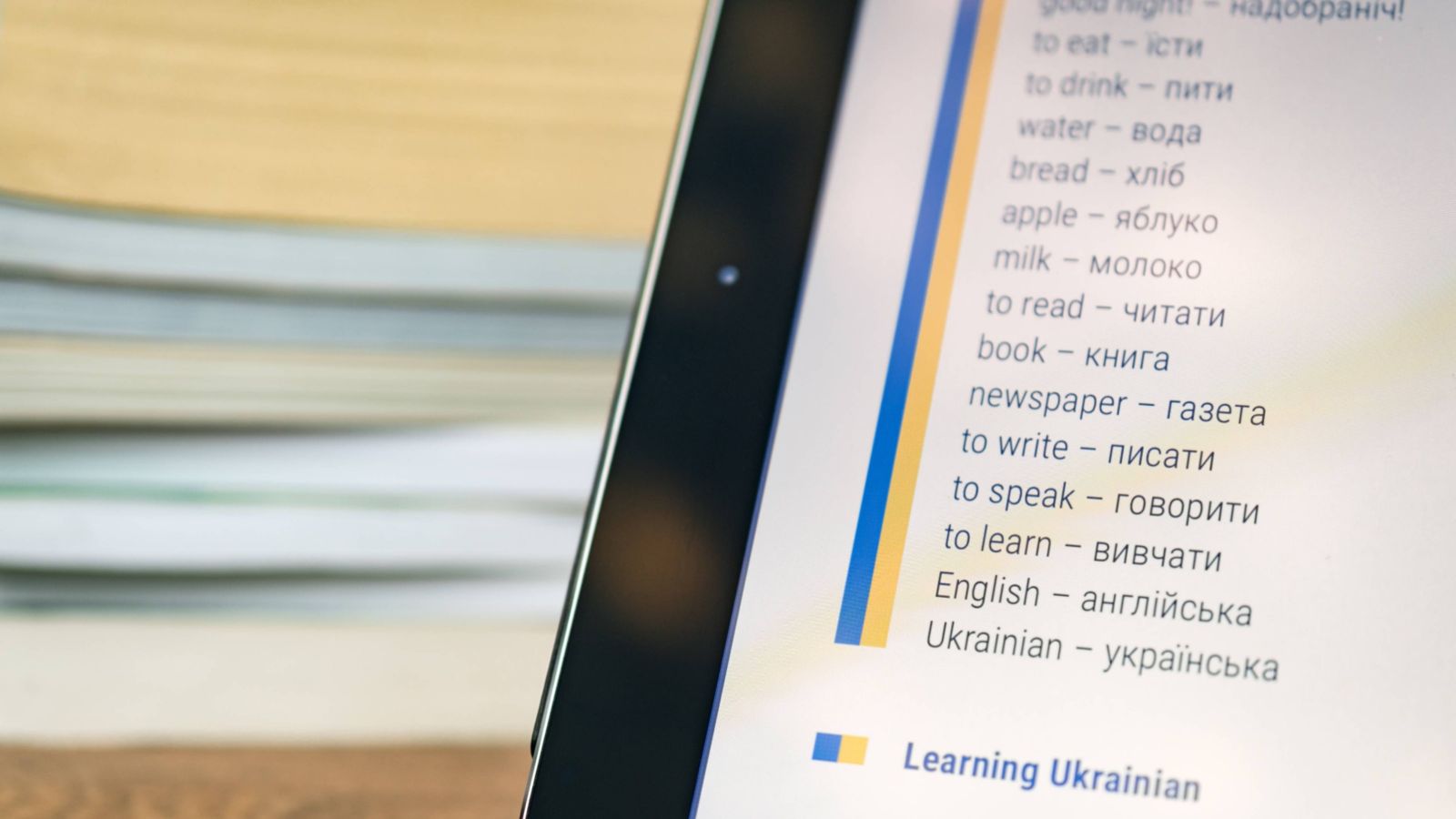

Those identifying with a national Ukrainian identity include those attempting to change their mother tongue (or dominant language they grew up speaking) from Russian to Ukrainian—in terms of the language they speak, the language in which they think, and the language with which they most identify internally.

This transition for the people taking part reflects a commonly discussed belief in Ukrainian life (and internationally) that there is a strong link between experience and language—as stated by activist Sergiy Osnach in 2015: “Language and historical memory are two interconnected identities.”

As a further example of this, one of the people I interviewed (Ilona, in her 30s, from Western Ukraine and now living in the United States), captured this ideological link when she talked about her ideal future self: “When I practise a conversation with my daughter in the future, I do it in Ukrainian, and it’s just when I think of myself in the future or just in general, the self-image of me in Ukrainian, it’s different than if I were to think of it in any other language. It just feels like home, feels natural as opposed to either Russian or English … It’s home. The language, Ukrainian language, is home. It’s childhood. It’s the sun … The person that I want to be, the person that does everything right and does everything the way I want to be, is the ideal person I strive to be, she speaks Ukrainian.”

The language situation in Ukraine has also taken a darker turn for some. Following the first demonstrations against then President Viktor Yanukovych’s pro-Russian government in 2013, many people reported feeling that Ukrainians who spoke Russian were “traitors”. From a political historical perspective, this is not entirely surprising, as language has been front and centre in Ukrainian politics for some time. For example, during the 2007 parliamentary elections, a billboard campaign in Crimea read: “Water. Roads. Language.”

It is important to note, however, that the ability and willingness to speak Ukrainian is not a requirement in the eyes of all the Ukrainians I interviewed. In fact, most, no matter where they were from or now lived, said it was much more important a person internally and consciously feels Ukrainian, regardless of the language they use.

Those with this belief also positioned themselves as part of a new multilingual, multicultural Ukraine where a person can speak whatever language they are most comfortable with and others will accept this. For them, language and identity do not have a one-to-one connection; it is much more complex.

Considering the many ways people identify, and their experiences with and ideologies about language, these young Ukrainians bring us a timely reminder that our understanding of and assumptions about people need to be continuously revisited. As people and societies develop and change, so too should our ideas about them.

Dr Corinne Seals is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Linguistics and Applied Language Studies at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington.