Our history

Read about the history of the IGPS, created to build a bridge between the university, the political community, the public sector, civil society and business.

Enduring public policy

It would be untrue to say that the Institute of Policy Studies came into existence because of Robert Muldoon's decision to destroy the future. But it would also go to the heart of the matter.

The Commission For The Future was a government-funded unit devoted to extending the time horizon of New Zealand's public policy planning. Like its sibling organisation the New Zealand Planning Council, it was established in the early days of the Third National Government, with a mandate to provide government ministers and ministries with policy recommendations that looked to the long-term good of the country: freed from questions of immediate political expediency, the expert policy workers appointed to both bodies would serve as a counterweight to the negative effects of New Zealand's three year electoral cycle.

Prime Minister Muldoon expressed his appreciation for the ideal of informed apolitical advice by abolishing the Commission For The Future in 1982. In that same year, he let it be known that he found certain recommendations from the Planning Council "unhelpful".

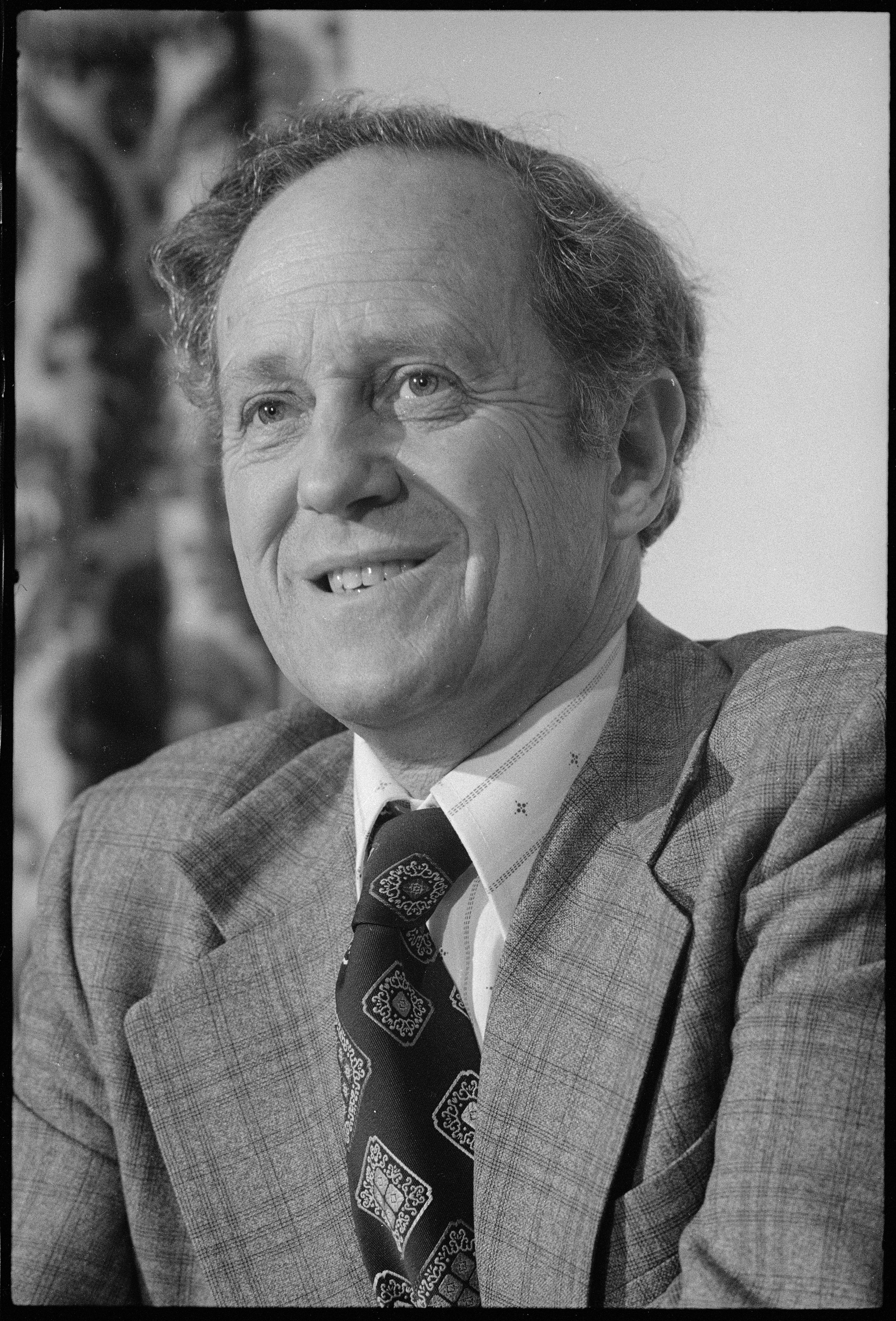

The chairman of the Planning Council in 1982 was Sir Frank Holmes, a major figure both in the local history of Economics as an academic discipline, and in the development of the policy ideal of evidence-based long-term public planning.

Holmes was among the growing number of people concerned that this model -- intrinsically a difficult one to sell to governments concerned with the always-looming question of re-election -- was dwindling to a wistful fantasy in the face of Muldoon's autocratic tendencies.

Two currents of thought

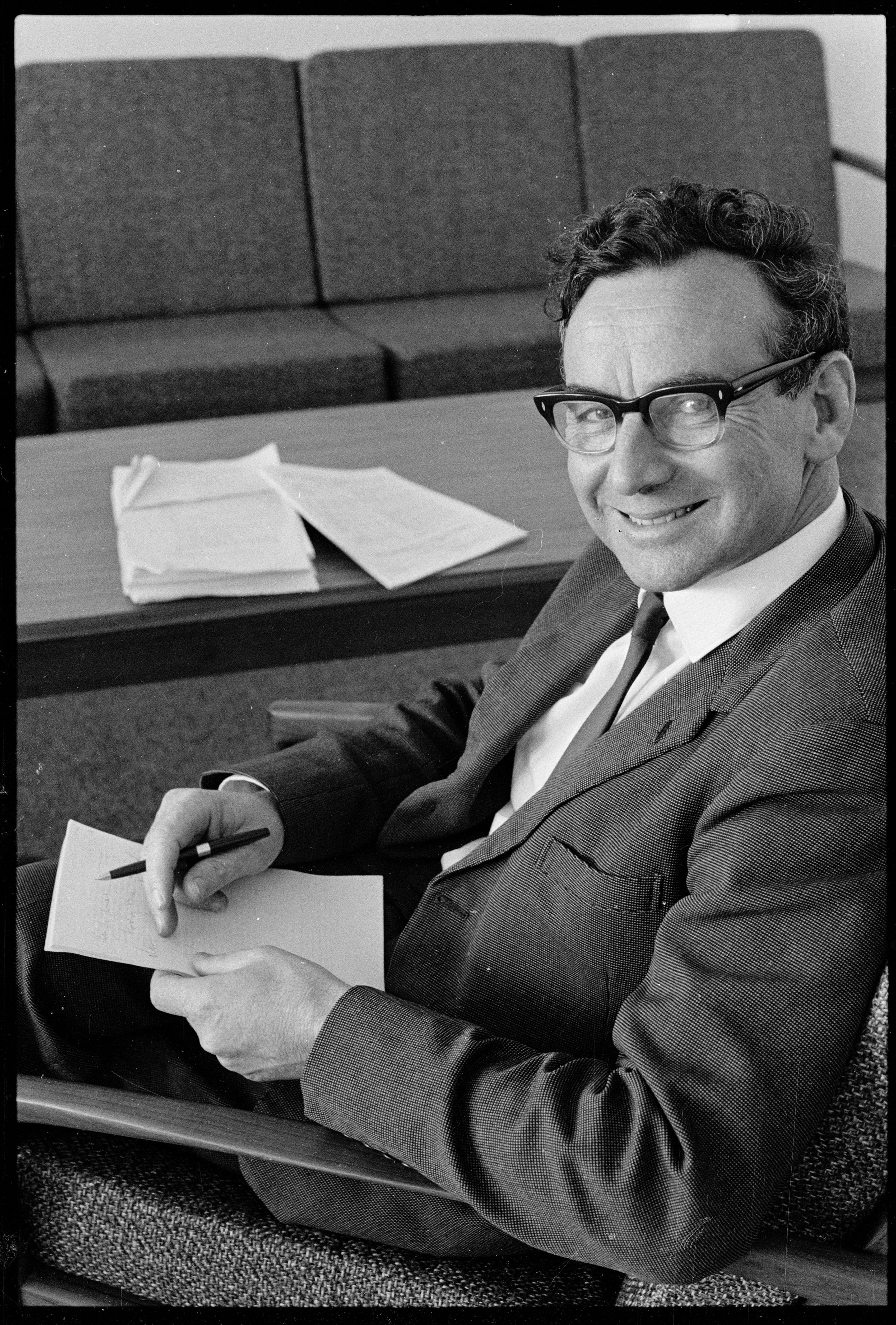

Another of these people was former Treasury head Henry Lang, who since his retirement from the public service in 1977 had been visiting professor of economics and convenor of the Master of Public Policy programme at Victoria University of Wellington.

Holmes and Lang were also united in the view that Victoria University of Wellington, at that time the only university in the nation’s capital, should be doing more to promote informed discussion of public policy.

In the wake of the Commission For The Future’s demise and Muldoon’s unsubtle hint to the Planning Council, these two currents of thoughts came together.

Lang and Holmes, together with John Roberts, Professor of Public Administration, paid a visit to Vice-Chancellor Ian Axford to discuss setting up a new body devoted to public policy.

The Institute of Policy Studies was established for an initial trial period in 1983, with Malcolm Templeton, who had previously been Deputy Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as its first director.

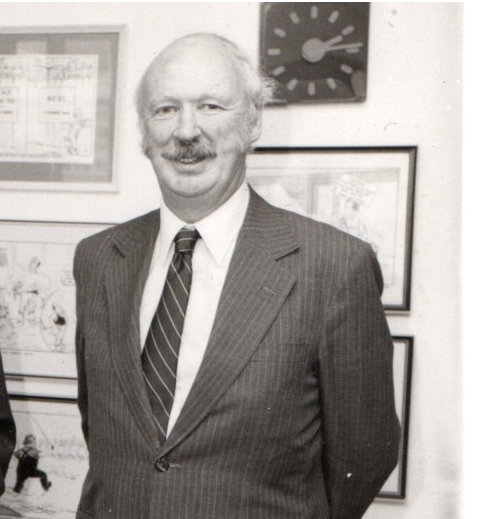

Gary Hawke, IPS Director 1986–1998, was by his own account “a peripheral figure” in these early discussions, many of which took place in the common room of the the University's economics department, where he taught.

“Frank Holmes and Henry Lang were the key figures at the beginning. The idea came out of a desire to ensure a free area for debate in the Muldoon era...

“They had a shared concern that open debate around policy issues was being closed down in Wellington as a whole, and the university was one of the places where you could expect the freedom of debate to continue.

“They sold the idea to the Vice Chancellor and the university council. That’s where the Institute of Policy Studies came from.”

An independent bridge

Professor Jonathan Boston, IPS Director 2008–2010, was also associated with the Institute from the early 1980s, having been seconded to it from the Treasury, where he worked at the time, as the first IPS research fellow.

“New Zealand hasn’t had very many think tanks. The idea behind the IPS was to establish a bridge between the university, the political community, the public sector, civil society, and business, that was the genesis of it.

“In the early days there was an advisory board, and on that board there were some very senior public servants, and people from the business sector, as well as senior academics; and the head of the Institute reported directly to the Vice Chancellor. That’s a very important part of the equation, the IPS was independent of faculties and departments and had a direct line to the Vice Chancellor, who funded it directly.”

The role of the Institute would be to initiate projects, to seek out people with the experience and insight necessary to contribute to them, and to provide a publishing outlet immune to political disfavour. This was an unusual model for the University, which is perhaps one reason the IPS was at first set up only on a trial basis.

The initial formal proposal to the Vice Chancellor underwent months of vigorous fine-tuning before it was approved (it would be cynical to use the wording “arm-wrestling with university departments who saw themselves as already engaged in forms of policy research and were hell-bent on patch protection”).

Henry Lang, with his extensive contacts across the public and private sectors, served as the first chair of the advisory board, and devoted a great deal of energy to bringing in top level researchers, whose work ultimately ensured that the new Institute earned ongoing support.

Radical policy changes

The IPS was therefore a product of the late Muldoon era in two intertwined senses. The fate of the Commission For The Future had demonstrated the need for policy research to be economically immune to political pressure. But in the early 80s there was also a growing sense across the Wellington political classes that radical policy changes were going to be needed soon across a range of areas, and that the essential preparatory work was not being done.

Henry Lang was able to bring in researchers from a wide variety of origins partly because he knew who to ask; but also because people were eager to be asked.

Gary Hawke: “There was no great antagonism to the idea of the IPS within the University, but the real enthusiasm for it came from downtown, from particular departments, like the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the State Services Commission, where there were people deeply in conflict with Muldoon.

“In 1983 it was obvious that there was going to be a substantial amount of debate over tax policy, for example, and so one of the initial projects in Malcolm Templeton’s day was around the introduction of GST, and Inland Revenue was very supportive of that.”

The Topic Committee

Over the nearly three decades of the Institute’s lifespan, before its 2012 reinvention as the IGPS, its directors developed many different mechanisms to open doors for researchers and ensure that their work remained both independent and relevant.

One was the Topic Committee, where people with an interest in a particular research area were brought together to help fund a project and provide advice on how best to proceed; this also ensured that when the research was published, the interested parties were primed to receive it and give an informed reaction. The reaction might be positive or negative, but in either case the effect was to move debate on the subject forward.

Arthur Grimes, IPS director 1998–2002, found committees of this form an effective mechanism for maintaining the Institute’s intellectual independence, as well as for securing funding and access.

“I would generally line up one or two players that I knew would agree to fund, say, ten thousand dollars, then I’d get everyone in the room and say to the ones I was sure of, okay, I wonder if you'd be able to front ten thousand dollars for this project... and then I'd turn to the others and say, would you be able to match that? That was my most successful funding model, because no one would have to put up very much, and that meant none of them felt like it was specifically their project. So if it happened to come up with anything they weren't entirely happy with, they weren't embarrassed.”

Club funding

“I had a lot of support from the public sector when I was director”, comments Professor Jonathan Boston, “particularly from key people like Mark Prebble, who was then State Services Commissioner, and Peter Hughes, then the head of the Ministry of Social Development.

“Mark organised a club funding arrangement for the Institute, what became known as the Emerging Issues programme, under which a series of projects were agreed by an advisory committee, which Mark chaired, and that committee organised funding, drawn from every government department and quite a few crown entities. They each chipped in a certain amount, depending on their size. In addition to that, various government departments sent us people on secondment—one researcher from MSD stayed with us for a couple of years.”

A home in the School of Government

In 2005, the IPS underwent the first of two major organisational changes when it was folded into Victoria University of Wellington’s newly established School of Government.

Arthur Grimes, in that year the immediate past director of the Institute, was on the working party charged with making recommendations for setting up the School of Government; he argued for the change because, in his experience, being answerable directly to the Vice Chancellor was an advantage only if you had a supportive Vice Chancellor.

“When I started as director I was reporting to Vice Chancellor Les Holborow, and he took a real interest in the IPS, he saw it as being of critical value for a capital city university.

“His successors, with the exception of Grant Guilford, did not see things that way—they did not consider Victoria University of Wellington as a capital city university and in their view it was just a university—and that made a real difference in the institutional support we received. So I felt that having a home in the School of Government was going to give the IPS more security. It had started to be a bit out on a limb.”

The Gama Foundation

The second and larger change came in 2012, as the result of a significant capital donation from the philanthropic Gama Foundation: the Institute was reconstituted as the Institute of Governance and Policy Studies, and given a far-reaching and highly specific charter to guide its activities.

Former IPS director Professor Jonathan Boston, who had left the Institute in 2010 over a matter of principle, was invited to serve as acting IGPS director, and subsequently appointed as director for a two year term. The Gama Foundation made a further major donation in 2015, to support the Institute's fulfilment of its charter goals.

Professor Jonathan Boston: “The IGPS has a slightly broader orientation from the IPS, being concerned with governance as well as public policy; the charter reflects the donors' particular concern for the integrity of the democratic process, and the need to ensure that the public interest is served in all areas of public policy, and that policy isn't hijacked by vested interests.”

For the 2013 to 2016 period, Professor Boston’s second tenure was followed by that of Associate Professor Michael Macaulay. Associate Professor Macaulay, who had previously been Deputy Director, bought issues of integrity, ethics, trust and anti-corruption to the forefront of the Institute’s work programme.

The Sir Frank Holmes Visiting Fellowship

In addition to the Gama Foundation’s endowment, and appropriately given his central role in founding the IPS, the IGPS also administers the Sir Frank Holmes Visiting Fellowship in Public Policy, an endowment set up by the children of the late Sir Frank.

The purpose of the endowment is to bring distinguished researchers and policy makers to New Zealand to contribute to public policy debate on major contemporary issues. Since its inception in 2012, there have been six Sir Frank Holmes Fellows: Greg Duncan, Dan Fiorino, Julia Black, Ross Garnaut, and Lavanya Rajamani, with the latest Fellow in 2017 being Alan Bollard.