Supporting invisible knowledges

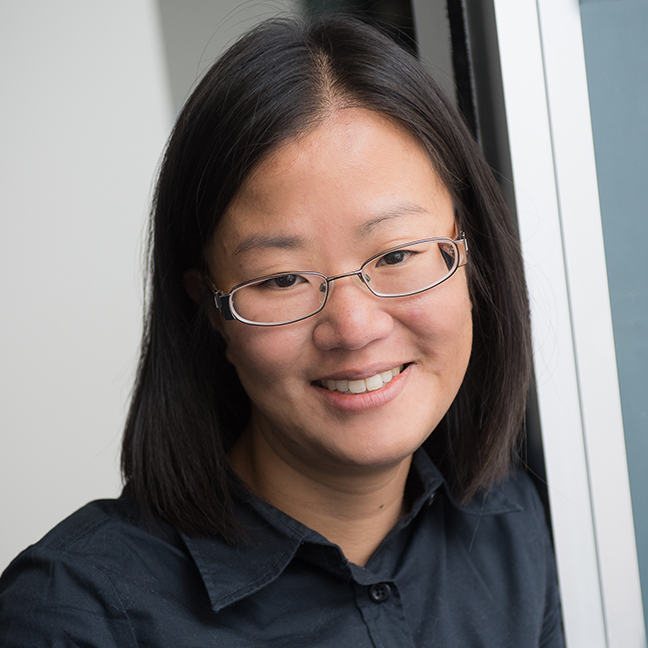

Professor Jessica Lai’s research is focused on seeing changes to intellectual property law that protect and support Mātauranga Māori.

Mātauranga Māori, the body of knowledge connected to te ao Māori, the Māori world view, Māori creativity, innovation and cultural practices, and knowledge associated with women, has traditionally been neglected by intellectual property law—Professor Jessica Lai’s research aims to change that.

Professor Lai, a lecturer and researcher in intellectual property law at Wellington School of Business and Government, has long been focussed on ensuring intellectual property laws support and protect the marginalised. Along with multiple articles, in 2014, she published a book, ‘Indigenous Cultural Heritage and Intellectual Property Rights’, dedicated to the subject. More recently in 2022, she published ‘Patent Law and Women’ .

“I’ve been working on mātauranga Māori and intellectual property for over a decade now. And it’s hard!” says Jessica. “There are a lot of moving parts and sometimes it feels like walking through a minefield. And researching intellectual property and women, I spend a lot of time just convincing people that there's a problem. But I stay in these spaces because it’s important and worth it.

“It’s the academic’s role to ask, and try to answer, the hard questions of what is the law doing? Who is it doing it for? What do we want the law to do? And in the context of mātauranga Māori, we’re talking about how the law reflects respect, understanding, partnership, and, ultimately, people coming together as a nation.”

While part of Jessica’s research focuses on developing recommendations to ensure existing law protects mātauranga Māori—this is only one part of what she wants to see changed.

“Mātauranga Māori is organic. It’s alive. What is needed is a system that acknowledges this and that fosters mātauranga Māori and the people and governance systems underlying it,” says Jessica. “Knowledge and culture are not static. This is a global truth. Yet, the western intellectual property system treats cultural products as discrete things. They are owned by individuals, whom you can approach for permission if you want to use them. In contrast, Māori view their connection to mātauranga Māori in communal and relational terms. This is just one of the many fundamental differences between intellectual property and mātauranga Māori. But, how do you bring these two systems together?”

Jessica believes the starting point for change is to recognise that the Māori knowledge system and intellectual property are both, at their core, about knowledge creation, curation and communication.

“We need to focus on the commonalities and try to bring the two systems into harmony, to reflect the spirit of the Treaty of Waitangi,” says Jessica. “This means, not just extending Western concepts over mātauranga Māori, but allowing mātauranga Māori to shape the law.”

While other countries also have similar issues with protecting and supporting indigenous culture and knowledge, Jessica believes that that protection of mātauranga Māori needs a uniquely New Zealand approach.

“One of the reasons why the western intellectual property system sits so awkwardly with mātauranga Māori is that it was developed for a different context. So, the best way to address mātauranga Māori and the specific concerns that it raises, will be through a locally tailored approach,” says Jessica. “New Zealand needs to do something that addresses the specific relationship created by the Treaty of Waitangi and the concerns of its people. One of the main problems New Zealand has is that it is too concerned with what is happening on the international stage, and it almost forgets that it has domestic tools to deal with the local situation.”

Ultimately, Jessica hopes her research will encourage people to think about these issues and how they can be resolved.

“Sometimes people forget that the law is a social construct. It reflects the culture, history and power dynamics of the context in which it was created. It is not intransient or immutable. When people start to think about the fact that intellectual property law was predominantly created by European Enlightenment-era males to protect their interests, they can start to think about how the law could reflect other ideals,” says Jessica.

This includes non-masculine ideals.

“It might seem unrelated, but it’s very related,” says Jessica. “The work is essentially about what it means when patent law was chiefly designed by Enlightenment-era Western males, and shows that patent law is gendered as well as racialised. Put another way, patent law – like all law – reflects the hegemonic power at play and this is to the detriment of the feminine and the non-Western, which are both invisible to the law.”